When Wegmans announced last September that it would no longer allow shoppers to use their smartphone to scan and pay for items in its stores, the company sparked a firestorm on social media among customers disheartened by the loss of convenience they faced as a result of the retailer’s unexpected move.

The East Coast grocery chain blamed unspecified “losses” stemming from the scan-and-pay service for its abrupt about-face on a program the retailer had trumpeted as a way to give people “the ability to shop how they want” when it rolled out the service in 2019. Wegmans suggested it might bring the service back if it could make “make improvements that will meet the needs of our customers and business,” without offering further details.

But while Wegmans concluded that letting shoppers use self-service checkout technology to breeze through stores came at too high a price, a host of other grocers, including Meijer, Hy-Vee, Giant Food and Kowalski’s Markets and Walmart, continue to offer scan-and-go as an option for shoppers looking to avoid traditional checkout lanes. In addition, other food retailers operating in the U.S. are in talks with vendors about potentially adopting the technology, according to industry officials.

One reason for that interest is that many shoppers have become so accustomed to using their phones to shop for groceries online and search for product information that the ability to use the devices to make in-store purchases is a natural next step, said Randy Crimmins, chief strategy officer of Stor.ai, which provides digital engagement technology to regional retailers.

Stor.ai also sees convenience-focused solutions like scan-and-go technology as a way for smaller retailers to stand out against larger competitors, Crimmins added.

“It’s such a fragmented consumer marketplace out there today that you want to make sure that you’re offering everything you can to appeal to your shoppers and make sure that you not only grow your shopper base, but your retained base, because everybody is nipping at you,” Crimmins said.

Crimmins’ company, which was known as Relationshop until it purchased the Israeli e-commerce firm whose name it now uses several weeks ago, has been working on a scan-and-go system for the past year and is now testing the technology with an unidentified retailer. Stor.ai intends to move ahead with a live deployment of the system later this year, Crimmins said, adding that the company sees scan-and-go technology as a way to reach more shoppers with features that let people access customized nutritional and other information about products.

Nico Müller, chief commercial officer of Shopreme, a scan-and-go technology supplier based in Austria, said his company has also seen interest in the service from U.S. retailers. The company has had conversations with a “large international retailer” that has a substantial presence in the U.S. about rolling out its system, Müller said.

Shopreme, has been offering scan-and-go systems since 2016, and the company’s technology is now in operation at about 1,000 stores in Europe. Shopreme’s clients include German supermarket chains Rewe, which began using the company’s scan-and-go system last year, and Penny, which adopted the technology in 2021.

“There are other parts of the experience that are more fun to focus on, but loss prevention is a big topic, of course, and it’s always the first question that is asked when speaking about mobile scan-and-go” with retailers.

Nico Müller

Chief commercial officer, Shopreme

Mining shopping patterns to stop shrink

Even as they promote the benefits of scan-and-go to retailers, Shopreme and Stor.ai are paying close attention to the drawbacks of the technology.

Müller said that while scan-and-go carries the inherent risk that shoppers might inadvertently or willfully neglect to scan items, Shopreme’s system is designed to mitigate the potential for shrink by analyzing shopping patterns to identify people whose activity warrants stopping them for an audit.

The system pays attention to factors such as whether a shopper has used scan-and-go at a given retailer in the past, their shopping history and the items they are purchasing, with a goal of keeping spot checks to a minimum to avoid unnecessarily inconveniencing consumers, according to Müller.

“There are other parts of experience that are more fun to focus on, but loss prevention is a big topic, of course, and it’s always the first question that is asked when speaking about mobile scan-and-go” with retailers, Müller said. “We have an engine that does nothing else than evaluating which customers to select without making it a hassle, because of course we want to have a smooth experience.”

Müller said Shopreme’s experience working with retailers in Europe is evidence that retailers can find ways to balance their interest in stopping theft with the benefit of offering shoppers the convenience of avoiding a checkout counter. “They wouldn’t have done this if they would see large losses there,” he said.

Crimmins said Stor.ai has also focused on developing methods to limit spot checks to people who are mostly likely to pose a theft risk as a way to avoid inconveniencing scan-and-go shoppers. The company’s approach to minimizing shrink is built around a retailer initially limiting the service to customers who are known to a store, and then gradually making it available to more people based on the retailer’s tolerance for risk, he said.

That method resembles the way Walmart handles its scan-and-go program. The retailer requires shoppers to be enrolled in its Walmart+ membership program, which costs $12.95 per month or $98 per year, in order to use the service.

“Most of our feedback from our testing and from other retailers that have [scan-and-go] applications is that the benefit of having scan-and-go outweighs the risk or the actual amount that they’re losing through fraud,” Crimmins said.

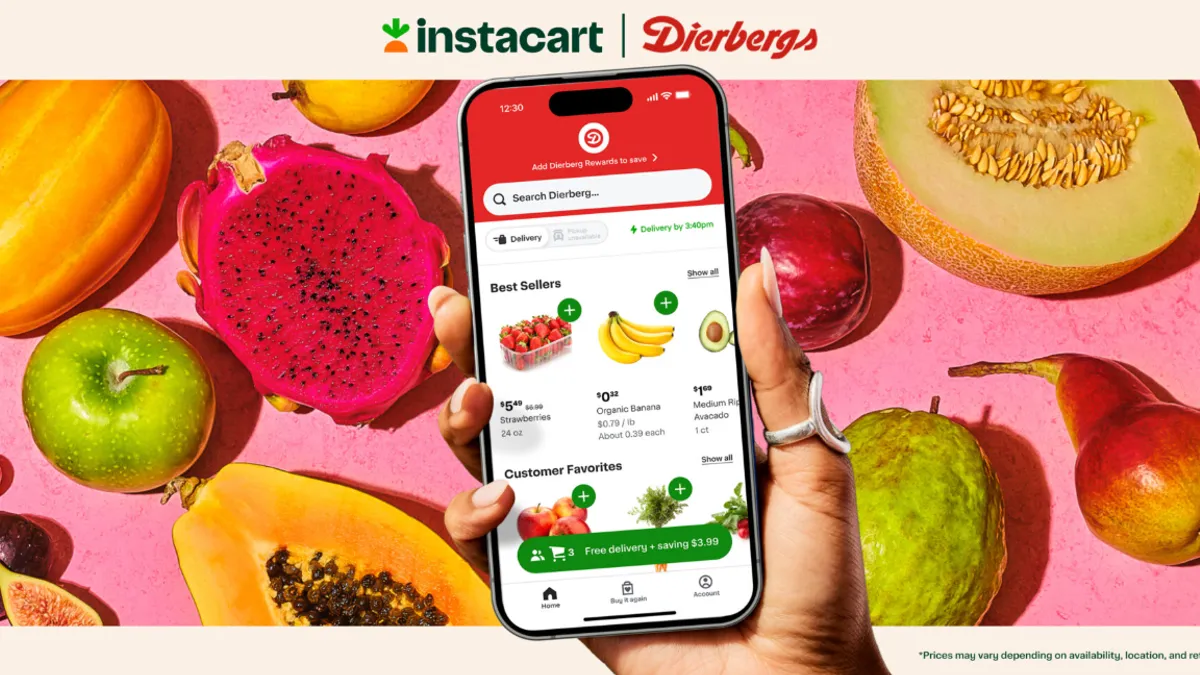

Instacart, which offers scan-and-go as a component of its Connected Stores suite of technologies for retailers, has also focused on developing strategies that keep shrink to a minimum without taking away from the speed and convenience that underpins scan-and-go, said David McIntosh, the vice president in charge of the initiative for the grocer-focused technology company.

Connected Stores also encompasses Instacart’s next-generation Caper smart carts, electronic shelf labels known as Carrot Tags, technology that provides out-of-stock alerts, list-making capabilities for shoppers, and FoodStorm, which allows consumers to order prepared food using in-store kiosks.

Instacart’s scan-and-go technology, which the company calls Scan & Pay, includes software that can identify shoppers who should be stopped for an audit based on factors such as how they are shopping, their scanning speed and whether they are familiar to the retailer, McIntosh said in an interview in September, when Instacart unveiled its Connected Stores initiative. Instacart’s approach to scan-and-go also involves equipping store employees with tablet computers they can use to monitor people’s behavior as they move around the store, McIntosh said.

Trust is a central issue

While checking selected customers’ orders might help keep people from walking out with items they haven’t paid for, making shoppers scan their items a second time can be seen by shoppers as intrusive, said Neil Stern, CEO of Good Food Holdings, a West Coast grocery chain that was the first to sign on to bring Instacart’s Connected Stores program into a supermarket.

Good Food Holdings has not yet committed to add scan-and-go capabilities to the store where it is piloting other technologies in the suite, Stern said.

“We do not have scan-and-go, and I don’t have any immediate plans to try” the technology in Good Food Holdings stores, said Stern, whose company runs several dozen grocery stores under banners including Metropolitan Market, Lazy Acres, New Seasons Market and Bristol Farms. “That doesn’t mean I’m negative on it. I just don’t have it in my IT plans for 2023.”

Stern said his cautious approach to scan-and-go stems in part from the audits that are baked into the concept. “It takes away a little bit of the customer experience you’re trying to provide,” he said. “It’s taking time or it’s saying, ‘I don't trust you,’ and neither one of those is the message you necessarily want to be sending out if you're using this product.”

Gary Hawkins, founder and CEO of the Center for Advancing Retail & Technology, said it isn’t clear whether shopper demand for scan-and-go is strong enough to justify the costs. “It’s something that was developed because technology enabled it, not necessarily because there was some huge shopper demand for that capability,” he said.

Hawkins added that he sees scan-and-go technology as a stepping stone to frictionless checkout solutions that use artificial intelligence-driven cameras to automatically identify and record items as people remove them from store shelves. While only Amazon has deployed the technology, known as computer vision, in full-size grocery stores, Hawkins said he expects more retailers to embrace it going forward as they look to amp up convenience without having to accept the risk people won’t pay for some items.

“That’s where I feel this whole space is going to wind up, simply because of the way it transforms the shopping experience and the multiple benefits that it brings to the retailer,” Hawkins said.

Müller, however, said he is not convinced that computer vision will overtake scan-and-go anytime soon because of the cost and complexity that accompanies installing the cameras and other equipment those systems require.

“For retailers, it’s a huge investment to set up a store” with a computer vision-based checkout system, said Müller. “And we think that mobile scan-and-go, if done well, is a great technology at this time, and I think it will stay so for a considerable time.”

Jeff Wells contributed reporting to this story.