Pardon the Disruption is a column that looks at the forces shaping food retail.

After the pandemic upended the grocery industry and the rest of the world in 2020 and 2021, everyone was due for a spell of normalcy. That’s not what happened, of course, as month after month of climbing inflation combined with significant supply chain challenges kept things unsettled for another twelve-month period.

Then the cherry on top came in October: Kroger’s proposed $24.6 billion acquisition of Albertsons — a mega-merger the likes of which the industry hasn’t seen in decades.

By this point, constant disruption has become the new normal for grocers. And while that’s no doubt been stressful for c-suite executives down to store cashiers, it has also made companies stronger by forcing them to confront areas like digital operations and worker benefits where they were previously coming up short.

It turns out that all this change has neither harmed the bottom line nor dampened companies’ spirit of innovation. Supermarkets reported robust sales this year as consumers once again embraced in-store shopping, and retailers are looking to keep the momentum going by launching new formats, new private labels and other innovations aimed at keeping shoppers filled up on meals and meal ingredients.

As grocers look ahead to another year and all of the challenges and opportunities that come with it, it’s worth looking back at 2022. Here’s what I’m calling the defining trends of the past year — and how they might fare in the year ahead:

Inflation went wild, but grocers held firm

Each month seemed to bring a round of fresh hell for consumers in 2022 as food prices ticked up and up and up. Grocers, who normally don’t mind a bit of inflation in the business, were left struggling to keep their customers shopping their aisles and not traipsing down to the nearby Aldi or Walmart.

Baskets shrunk, and so did trip frequency, but grocers by and large were able to prevent a major exodus from their stores — a testament to their merchandising acumen, product assortment and their ability to push targeted promotions to customers. This was also a testament to the strength of U.S. consumers. Witness the string of strong earnings statements from companies like Kroger, Ahold Delhaize and Weis Markets in recent months.

Inflation is starting to come down, which would seem like a good sign. But it may not be coming down quickly enough for consumers who have endured more than a year of frustratingly high prices. Walmart CEO Doug McMillon noted during the company’s earnings call in November that the retailer is seeing more high-income shoppers — indicating financial pain is being felt up and down the income ladder.

It’s hard not to see that shift continuing in the months ahead if inflation continues to creep, rather than slide, downward.

Loyalty programs leveled up

How important has having a robust loyalty program become for retailers these days? So important that even Walmart — the company that has long believed its everyday low prices are all the incentive shoppers need — has one now.

In an industry where sameness abounds, loyalty programs are one of the few ways grocers can stand out. And as digital shopping, including smartphone-powered shopping, continues to grow, retailers are waking up to the creative possibilities out there. The Fresh Market’s humbly named Ultimate Loyalty Experience program launched early this year offers members-only pricing, purchase frequency rewards and a free slice of birthday cake. Seven months later, it surpassed a million members.

2022 also saw the growth of a few loyalty programs tailored to e-commerce, including Kroger Boost. As retailers continue building out their online platforms, loyalty programs offer a way to drive volume and complement the store shopping experience — not to mention, nab precious consumer data.

Kroger is not messing around

The nation’s largest supermarket chain is not content with that title alone. It wants to become a retail force on par with Amazon and Walmart.

That conviction was evident when Kroger linked arms with Ocado back in 2018 in a deal that essentially bets the house on planned delivery as the future of e-commerce.

And the company once again underscored that drive this fall with its $24.6 billion bid to acquire close rival Albertsons. The mega-merger has months and months of regulatory red tape ahead of it. But if the deal goes through, the resulting company will be much more than a supermarket operator — it will be an omnichannel juggernaut capable of setting the pace for all of food retail to follow.

E-commerce got more complicated

Online shopping sales markedly decelerated this year after soaring to previously unimaginable heights in 2020 and 2021. But there were areas where e-commerce continued to show considerable strength.

According to Brick Meets Click’s always-interesting monthly sales estimates, the pool of consumers who regularly buy groceries online — what the firm calls monthly active users, or MAUs — expanded this year, indicating that e-commerce continues to be an important way to reach an expanding group of highly engaged, digitally savvy shoppers. The MAU base in October, for instance, grew 10% this year over last year, according to Brick Meets Click.

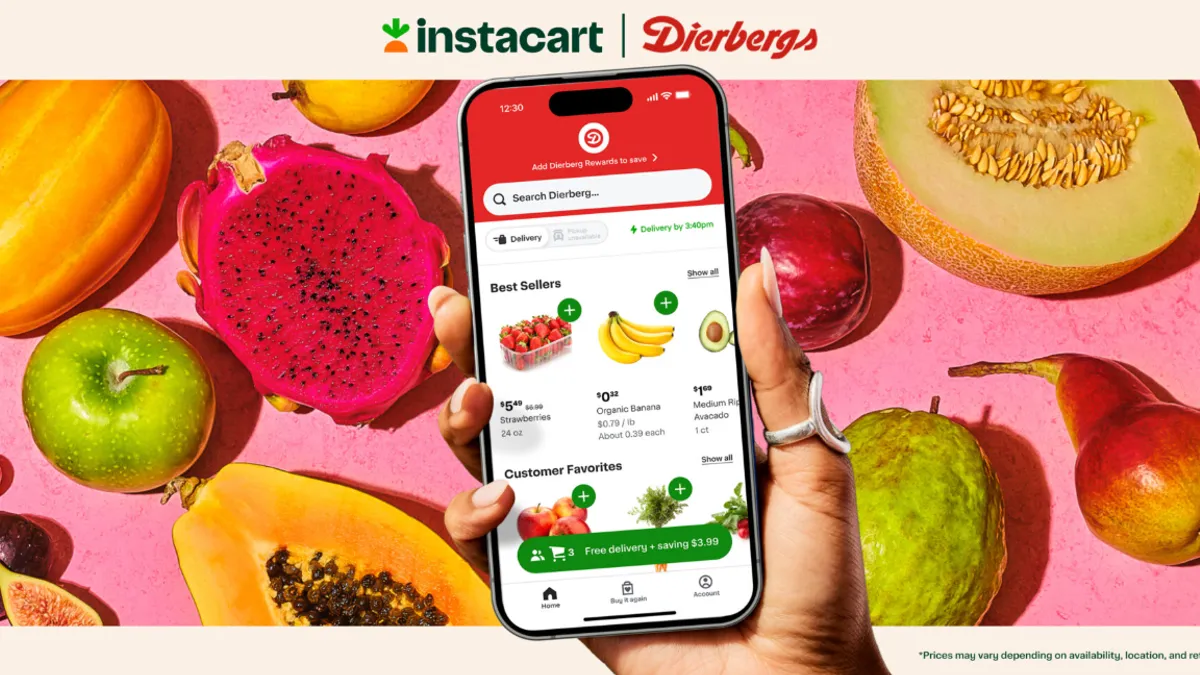

And even though sales came down in 2022, retailers still pushed ahead with efforts to establish their own proprietary online platforms and reduce their reliance on marketplace companies.

As inflation tapers off, I expect we’ll see online sales rise again in 2023.

Retail media galloped ahead

On the last day of the Groceryshop conference this fall, I attended a retail media session that was absolutely packed. This was quite a feat, considering the last day of Groceryshop is often sparsely attended, with many attendees having already flown home.

I wasn’t surprised at the turnout. In the low-margin grocery business, retail media offers the tantalizing prospect of a new, fast-growing revenue stream. Large grocers like Ahold Delhaize and Albertsons that formerly relied on partner companies to manage their digital media capabilities have brought those responsibilities in-house. Smaller grocers like Woodman’s Market, meanwhile, are linking up with media firms to launch their own digital ads businesses.

Even though grocers are seeing dollar signs ahead, they’ll have to fight hard to win advertising dollars away from companies like Kroger, Amazon and Instacart that already have well-oiled media networks in place.

Grocers are still boldly exploring new formats

Opening new store formats is tough work for grocers, requiring them to push out of their comfort zone and go up against a new class of competitors. But the need to stay relevant with shoppers and grow in what’s become an over-stored industry is forcing retailers to continue trialing new store experiences.

Smaller, uniquely branded stores have been a pronounced trend in recent years that continued to roll along in 2022. Schnucks, which has recently opened a “Fresh” store as well as a specialty outlet called Eatwell, resurrected its “Express” convenience brand in September. Save Mart also just opened its first small-format store, while Meijer officially unveiled a grocery format that, while not small by any means, is smaller than the company’s hulking supercenters.

I do wonder if in 2023 we’ll see new store formats go digital-only. We’ve started to see companies like Kroger and Publix do this with quick delivery in partnership with Instacart. Digital storefronts offer a less capital-intensive way to trial new ideas and drive innovation.

Simple Truth Market seems like a solid idea to me. (You’re welcome, Kroger).

Checkout innovation is still a mess

When Wegmans axed its scan-and-go service this fall, we saw a heated debate bubble up, not just among shoppers, but among industry experts, as well.

Was Wegmans short-sighted for getting rid of a program that so many consumers felt so passionately about? Or was it prudent for halting a service that saw too many people walk off with products without paying for them? We saw plenty of people arguing on both sides.

To me, the news highlighted a deeper point: Grocers still don’t have a good solution for one of the biggest shopping headaches out there. Scan-and-go programs may be too much of a liability for some grocers and not popular enough for others. Self-checkout terminals, meanwhile, have proliferated across stores recently, but that’s a move aimed more at labor savings than at delighting shoppers. Research shows a lot of people still don’t like self-checkout.

Fully frictionless checkout technology may be the final answer, but that’s still years away from scaling in grocery. Until then, I’ll continue to wait in line.