Pardon the Disruption is a column that looks at the forces shaping food retail.

The tech geek in me gets really excited when I think about all the digital enhancements that grocers have made to their stores recently and will continue to make in the years ahead.

Electronic shelf labels, shopping apps, ordering kiosks, new checkout technology, smart carts, video screens and more promise to make stores more connected and efficient. Over the next decade, we’ll see supermarkets change dramatically as they look to plug into the omnichannel shopping revolution.

With these updates, retailers can save on labor costs by automating key jobs. They can also gather and monetize valuable consumer data. Retail media, for one, has netted millions for companies online and promises to generate even more revenue as innovations like sampling kiosks and personalized promotions make their way into stores.

Consumers also ostensibly benefit from all of this by having a more streamlined shopping experience. But retailers should not overlook the inevitable concerns that come with these updates.

A recent dust-up over electronic shelf labels (ESLs) highlights my point. Following Walmart’s announcement in June that it will add ESLs to nearly half its U.S. stores over the next two years, consumers and media outlets began questioning whether the technology’s ability to quickly update shelf prices would result in a Wild West of ever-changing product prices.

As Fast Company put it: “Digital price tags could, in effect, allow Walmart to utilize a strategy that’s become known as ‘dynamic pricing,’ which more or less means that it can change the price of items on the fly.”

According to this thinking, dynamic pricing could turn grocery shopping into something akin to buying Uber rides and air travel, with prices throttling up and down based on consumer demand, supply, weather and other conditions. Retailers could hike the price of bottled water before a severe storm hits or make consumers pay double for Thanksgiving turkeys the day before the big holiday. A shopper could pick up a jug of milk when it’s one price, then see a different price flash across the register when they check out.

Walmart, for its part, told Fast Company it does not engage in dynamic pricing and would only adjust prices for rollback and clearance items.

Fears around dynamic pricing took a major toll on fast food chain Wendy’s earlier this year. After the company announced in February that it would test dynamic pricing at some of its stores, the outcry was swift and loud as inflation-battered consumers balked at the idea of possibly paying more for a Junior Bacon Cheeseburger when demand is high. Wendy’s contended it didn’t want to raise prices — it just wanted to lower them to spur demand. Nevertheless, this point got drowned out and the chain had to abandon the test.

Adding to the pile-on, two U.S. senators sent a letter to Kroger last month pressing for answers regarding the company’s use of ESLs. Sens. Elizabeth Warren and Robert P. Casey wrote in an Aug. 5 letter that the digital equipment allows stores to “calibrate price increases to extract maximum profits.” Kroger responded that ESLs are only used by the grocer to lower prices on products. “To suggest otherwise is not true,” the company wrote.

Walmart, Kroger and Wendy’s all sent clear messages that they’re using their programs to lower prices, not raise them. The problem is that these messages were reactive rather than proactive.

In its announcement about ESLs rolling out to more than 2,000 stores, Walmart played up how much more efficient store operations would become as workers freed up from manually updating price tags. It didn’t directly address the all-too-predictable concern that faster, automated price updates could allow the company to raise prices and gouge consumers.

This challenge of explaining the ins and outs of complex store technology doesn’t just apply to ESLs. Throughout the store, retailers are making updates that provide operational benefits to them but don’t offer clearly defined benefits for shoppers.

Self-checkout, which is essentially a labor-saving tactic for retailers, is a pain in the neck for lots of shoppers. In addition, many consumers — myself included — struggle to see the point of placing a digital screen between them and their favorite beverages.

Digital changes rolling out in grocery stores can be very visible and disruptive, touching on sensitive topics for shoppers like privacy, pricing and the integration of complex technology into everyday habits.

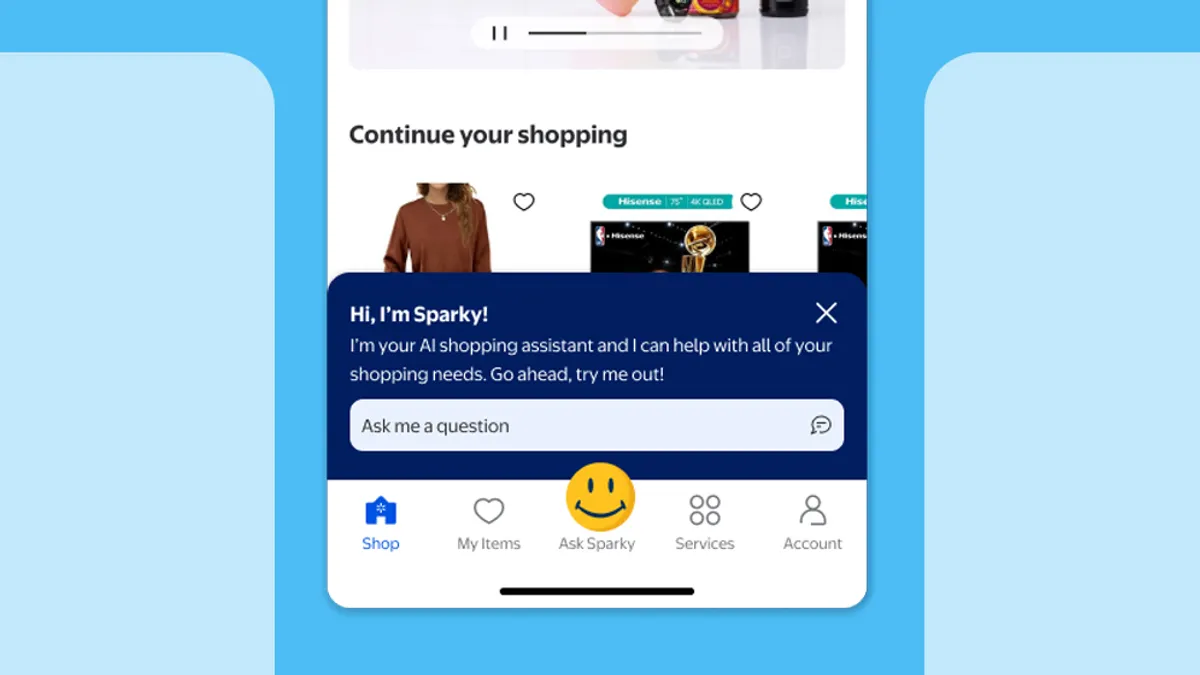

Shoppers have made no secret of their distaste for clunky app updates and self-checkout terminals outnumbering staffed registers. Retail media could also become a point of contention for shoppers as in-store video screens, smart carts and smartphone-enabled shopping become more prevalent.

In retailers’ perfect-case scenario, shoppers get tailored promotions sent to their phones or smart carts that help them save money while browsing. In reality, I think we’re going to see a lot of shoppers getting frustrated at all these ads and the tools companies use to track their engagement.

Retailers should be ready for privacy concerns to accompany the store digitization trend. In their letter to Kroger, Warren and Casey brought up the retailer’s use of facial recognition in its shelf EDGE technology to help determine information about its shoppers like gender and age, writing that they are “concerned about whether Kroger and Microsoft are adequately protecting consumers’ data.”

Grocers have several options to proactively educate shoppers and address concerns, from strategically placed signage to information on their websites, such as their frequently asked questions pages. They can provide a phone number or email customers can contact to share concerns or ask questions.

The most effective tool, however, may be store workers.

Nearly two years ago, Lowes Foods introduced a new app that offers online shopping as well as tools to enhance in-store shopping. The update was significant and so was the onboarding process: Instead of their current app just updating, shoppers had to download the new app and set up a password to access it. A lot of them would probably be confused and upset by the change, executives figured.

So Lowes decided to have employees in every store dedicated to helping shoppers navigate the process. Product sampling stations got refashioned into impromptu tech support desks. To spur interest, Lowes offered a $3 digital coupon on a dozen eggs.

When the $3-off coupon hit, shoppers predictably flocked to stores and found staff members waiting for them, ready to help add the new app and answer any questions.

“We didn’t just go out there with a digital coupon,” Lowes President Tim Lowe told me last year. “We put together a whole playbook for our stores.”

As retailers continue to add digital enhancements to their stores, they’re going to need to develop a playbook for not just integrating these systems, but also for helping customers navigate the changes. And human interaction, ironically, may go a long way toward making that happen.