Pardon the Disruption is a column that looks at the forces shaping food retail.

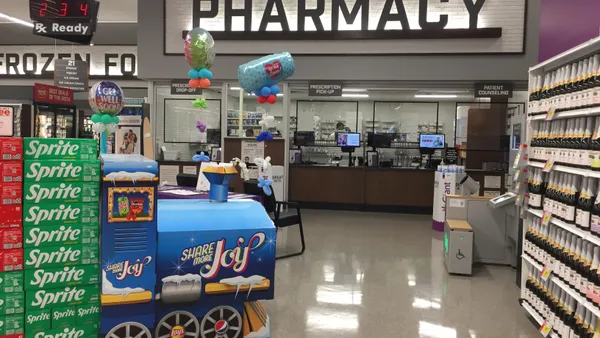

For years, in-store pharmacies have been the face of health for many grocers. They're the places where shoppers can pick up their prescriptions, or stop in for a flu shot or wellness visit, and where companies center wellness messaging that can echo throughout the rest of the store.

Unfortunately, pharmacy has become a complex and costly venture for food retailers. Hy-Vee, which operates around 300 stores in the Midwest, recently said it has had to pay more than $100 million in remuneration fees so far this year. Some grocers, particularly small operators and regional chains, have exited the business.

For the grocers that do still operate pharmacies, these health destinations have been vital pandemic resources, doling out everything from vaccines to COVID-19 testing kits. This has helped draw in new shoppers, and the loyalty benefits of being a regular stop for prescriptions are no doubt helping stores as inflation weighs on consumers’ wallets.

But for all it has done for retailers, and for all the ways it has changed, the grocery store pharmacy has always been at odds with its surroundings. Customers who are diabetic or who are coping with high blood pressure, for example, will stop by the pharmacy to pick up their medication, then walk past aisles of fresh foods that medical science overwhelmingly shows can help manage these conditions — and yes, unhealthy foods, as well — without any effort from the retailer to connect the two resources.

Food is a powerful health tool. This should come as no surprise to grocers, many of whom have expanded marketing campaigns and labeling programs that promote better-for-you foods and services. What they may not be aware of, however, is the growing emphasis the medical community is placing on preventive medicine and the role of foods and beverages in staving off, and even helping treat, chronic disease.

Study after study has supported the notion that food plays a vital role in preventive health and the management of certain conditions. And a growing body of research is pointing to opportunities for government, insurers and private companies to expand programs like produce prescriptions for communities, including those without easy access to fresh, nutritious foods. This presents grocers with a budding opportunity to offer new services and forge partnerships that focus on food as a health resource, even if they don’t operate pharmacies.

As I wrote last week, Kroger has recently embraced the food as medicine movement, with everyone from its CEO to its dietitians promoting the notion that the groceries it sells can play a vital role in healthy diets as well as the management of medical conditions. The company offers a health app, telehealth appointments with dietitians and other resources, and as it continues its digital march, I expect we'll see much more from it on this front.

Grocers are thinking a lot more in terms of ecosystems these days — particularly in digital, where they’re tying together online shopping, marketing and consumer data to create a network loop of operational benefits. Now, what if they could take that same framework and apply it to creating a health ecosystem centered on their stores?

Imagine a future where shoppers get a discount on their health insurance premiums for following a health app run by a grocer, or where people with diabetes get referred by their doctor to a grocery store and its health platform.

"I think we're going to see an accelerating convergence between food and health care. And I think we're going to see incentives being brought to the table by payers and health insurance companies," Gary Hawkins, founder and CEO of the Center for Advancing Retail & Technology, told me recently.

Food as medicine meets digital innovation

Health and nutrition guidance is nothing new to food retailers, of course. For years, they’ve offered dietitian counseling and medical visits through their pharmacies and store clinics. They’ve promoted healthy recipes on their websites, put up shelf tags and developed nutrition labeling systems that score the healthfulness of items according to numbers, letters or even by stars.

These efforts have been earnest and, in some cases, very innovative. But they’re also confusing (what separates a product with two stars from one that has three?), require too much work on the part of the shopper, are under-promoted and often appear as one-off services rather than parts of a cohesive strategy.

Some companies have tried to fashion more comprehensive health programs. Nearly 20 years ago, Lund Food Holdings started selling a $99 DNA testing kit that shoppers could use to help fashion an individualized diet plan. But it required shoppers to review a custom report, which ran around 30 pages, and then receive follow-up guidance with Lunds' dietitians.

Advances in medical science and digital technology are making health programs more convenient and cost-effective, and possibly even more effective as well. These range from e-commerce tools that allow shoppers to filter product listings to precision nutrition programs that incorporate artificial intelligence and health markers to determine personalized dietary regimens. A few grocers, like Schnuck Markets, Kroger and Niemann Foods, have rolled out apps that offer health guidance and rewards that, while not exactly revolutionary, have opened the door to personalized health guidance by retailers.

Allison Primo, health and wellness strategy manager with Schnucks, told me that the health guidance tools the company has rolled out over the past several years have been well intentioned but confusing. The grocer put up shelf tags identifying products as “sodium smart,” “sugar smart” and “dietitians pick,” for example, but shoppers said they didn’t really know what to make of the labels.

“We really took a little bit of a step back and said, OK, we have various attributes out there provided to customers, but they're still confused,” she said.

She and her team began working with technology firm Spoon Guru on a personalized scoring and rewards program called Good For You that went live in January and is on pace to hit 50,000 members by September. She hopes the service will offer even deeper guidance, like custom meal planning, in the future.

If programs like Good For You can eventually guide shoppers to healthier choices and effectively help them with managing conditions like diabetes, they could tie in with insurance companies, employers and healthcare providers. This could offer a major boost for grocers at a time when they’re desperately trying to win shoppers' loyalty.

"I think we're going to see an accelerating convergence between food and health care. And I think we're going to see incentives being brought to the table by payers and health insurance companies."

Gary Hawkins

CEO and founder, Center for Advancing Retail & Technology

How Heinen’s is testing its ‘pharmacy of the future’

The retailer that’s doing the most in this area right now isn’t a national chain. It’s a modest-sized regional grocer based in Ohio.

Years ago, Heinen’s considered whether to open pharmacies inside its stores. It wanted to be able to compete with other grocers that either already had pharmacies or were adding them. But the company ultimately decided to pass on the opportunity because it didn’t feel like filling prescriptions fit with its mission as a food retailer, said Chief Innovation Officer Chris Foltz.

“We wanted to sell food, not [prescription] drugs,” he told me.

Heinen’s kept looking for ways to tie the food it sells to preventive health, dieting and disease management. It hired a chief medical officer more than a decade ago. It also opened wellness centers inside its stores filled with vitamins and supplements, and staffed dietitians and nutrition counselors who could advise shoppers.

But even with those resources, shoppers said they were still confused about what they should eat to lose weight and manage conditions like gluten intolerance and diabetes. Last year the company rolled out a nutrition guidance program and health membership club called Club Fx. Then in January, it opened its Personalized Nutrition Center, an in-store clinic where shoppers can pay $300 for a proprietary testing regimen that helps determine an individualized diet plan in line with their risk factors, health goals and other factors.

I can’t speak to the effectiveness of Heinen’s nutrition center, which also offers dietary guidance that doesn’t involve pricey medical testing. But I think it’s worth noting and paying attention to for a few reasons.

First, the testing program and Club Fx embrace the idea that food plays a central role in helping shoppers' manage their health. And it takes that approach a step further by offering a system that interested shoppers can follow in detail. In other words, it does more than just offer some recipes and a pat on the back.

Second, the program aims to become one part of a network that connects services, products, health professionals and outside companies. The center ties its guidance to the Club Fx system and the products labeled under that program. And both of these resources are looking to connect with employers as well as insurance companies that are trying to incentivize people to eat healthier.

Lastly, Heinen’s program effectively leverages a partnership to provide its new testing service. The clinic is administered by VitalHealth Partners, a medical practice run by Heinen’s chief medical officer, Dr. Todd Pesek, thus helping Heinen’s avoid the compliance and legal hurdles that would come with building a service like this from the ground up.

As technology companies and the medical community drill down further into preventive health and utilizing food as medicine, grocers should consider opportunities to forge partnerships and build out networks. For those that operate pharmacies, these facilities could become the entry point for these expanded services — or at least a key piece of the network.

For grocers that don’t operate pharmacies, this could be an opportunity to position their stores as a vital health resource.

“It was just natural for us to say we want to be the pharmacy of the future, food is medicine, and make this investment,” Foltz said.