Nearly twenty years after Webvan flamed out spectacularly, founder Louis Borders is giving online grocery another go.

His new venture, Home Delivery Service, comes out of stealth today and plans to go live in San Francisco sometime next year. The tech-heavy company will offer same-day delivery on a full assortment of grocery products, with no added fees, a no-tip policy for drivers and no subscription required. It will also sell general merchandise and plans to eventually sell made-to-order food and products from brands including Ray-Ban, Adidas, Burberry and Apple.

Borders equated the experience to shopping at a European hypermarket, with the plan of ultimately selling about half groceries and half general merchandise, all at mass-market prices.

“We're taking an end-to-end approach to resolve some of the main issues in e-commerce, starting with fresh groceries,” Borders, who also founded the defunct Borders bookstore chain, told Grocery Dive.

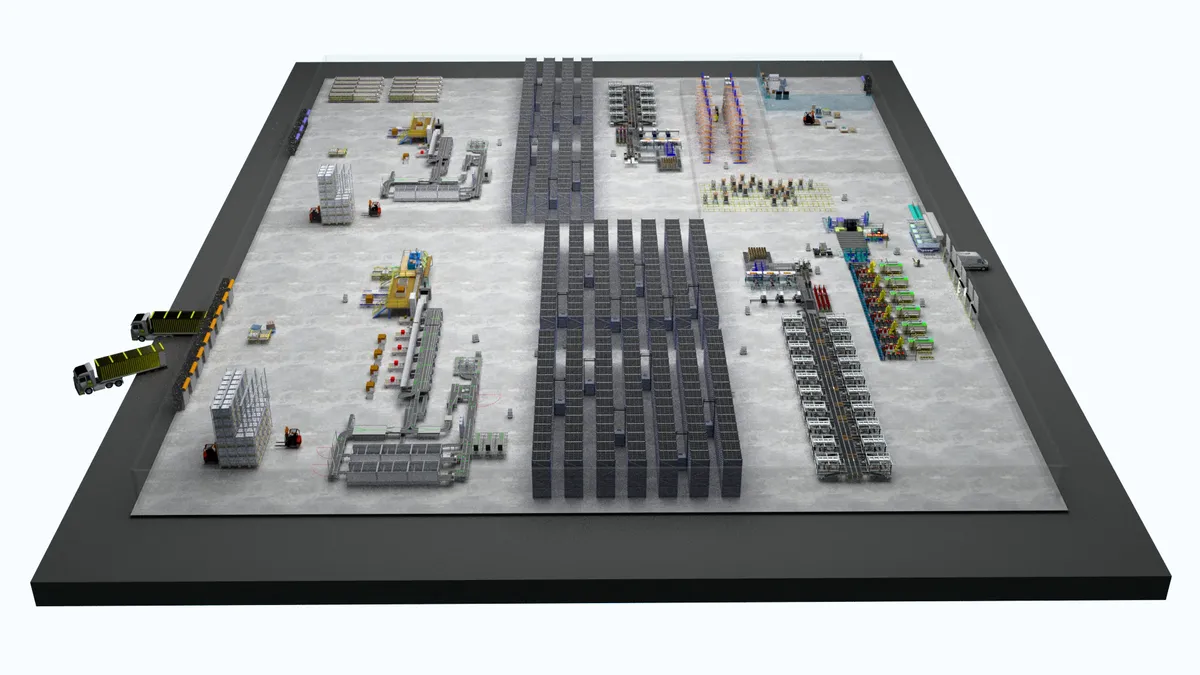

At the core of that claim is an automated fulfillment system that will use an army of robots to assemble online orders. This includes mobile units that transport inbound products, rolling bots that shelve and unshelve them, and picking arms that assemble orders, all across a 150,000-square-foot warehouse. Borders said 95% of products can be picked and packed without touching human hands, and that the system keeps frozen, fresh and shelf-stable products at a consistent temperature from the time they enter the facility to the time they reach shoppers’ homes. The fast-turn model means perishable goods like produce will only be in the facility for about a day before getting routed into an order.

Each warehouse, which staffs around 60 employees compared to the 200 who worked in Webvan's fulfillment centers, will hold around 100,000 products. But the company’s marketplace will be eventually be larger than that. Shoes, apparel and other listed goods not stocked in the warehouse can be brought in as customers order them, and the facility will automatically route them into those orders.

“You won’t get same-day service in that case, but you’ll get the convenience of one-stop shopping,” Borders said.

Borders said Home Delivery Service has spent the past several years researching and developing the proprietary technology that will go into its facilities. Each warehouse will sell an estimated $200 million worth of goods annually, with around $100 million of that in groceries — equivalent to around four supermarkets, Borders said. The company’s ten-year plan calls for about 100 automated facilities serving major metropolitan areas all over the world.

Home Delivery Service hopes to win over shoppers with its front-end service as well. Its delivery drivers will be full-time, intensively trained employees who in addition to schlepping orders will also process returns, answer customer questions and take advantage of any sales opportunities. It’s a holdover from the days of Webvan.

“Webvan had that personal touch at the point of delivery, and people really liked that,” said Borders. “It eliminates the need for call centers and return centers. It's bringing a retail store service experience to home delivery.”

The company’s ordering platform, meanwhile, will personalize assortments for shoppers based on their dietary preferences and restrictions. And each order will come in reusable tote bags that customers can unload, collapse and then return to their driver when they receive their next order. The totes will be taken back to the warehouse and sanitized before being used again.

Is it Webvan all over again?

Establishing a plain-sounding new brand in online grocery at a time when major chains like Amazon, Walmart and Kroger are speeding toward the same opportunity might seem like folly — particularly for someone whose previous venture in the space is held up as a cautionary tale for e-commerce businesses.

More than 20 years ago, Webvan burst onto the public market with a $1.2 billion valuation. But the fast-growth, mass-market model was flawed, and the company was weighed down by pricey infrastructure, including a network of high-tech fulfillment warehouses. Webvan went out of business in 2001, and ever since has been viewed as a casualty of the dotcom era and an example of an online grocer that tried to grow too fast.

It’s not hard to see parallels between Borders’ former venture and his current one: the pricey end-to-end infrastructure and service model, the ambitious growth plan. The one-stop shopping concept is different, but it’s not unique, with Target, Amazon and Walmart and even grocers like Hy-Vee offering a wide assortment of products online.

Home Delivery Service is also going up against a rapidly automating fleet of grocery competitors deploying everything from large-scale sheds to micro-fulfillment facilities. Kroger will open its first giant automated warehouse in partnership with Ocado next year — the first of 20 such facilities — while grocers like Albertsons and Walmart are piloting micro-fulfillment centers attached to stores. Amazon is rolling out new grocery brands, buying up real estate and expanding its Amazon Fresh online service to new markets over the past year.

But Borders insists consumer demand has finally caught up to his e-grocery ambitions. Online orders have taken off during the pandemic, and experts agree many shoppers will continue using services like Peapod and Amazon Fresh long-term. The sharp increase in orders has also strained many retailers’ fulfillment systems, making an even stronger case for the use of automation in the future.

“Although grocery has been a laggard in e-comm as a category, it’s not going to be a laggard for much longer,” Borders said.

Home Delivery Service will offer a price contrast to fee-based services like Instacart and Shipt, and sell fresher food than brick-and-mortar grocers can deliver due to its fast routing system, he noted.

“I think demand far exceeds supply, even with the broken services today,” he said. “If you do a $200 order on Instacart, there’s about $40 in fees, including subscription fees, delivery and product markup. We can sell you that same order for $160.”

The company has raised $30 million so far, including investments from non-compete companies like Toyota and Ingram Micro in exchange for the right to use Home Delivery Service's proprietary automated fulfillment system. Borders said he anticipates a Series A funding round will close quickly, after which the company will get to work building its first fulfillment center in South San Francisco.